Evolution of Recombination Hotspots in Vertebrates

In collaboration with: Prof. Francisco Úbeda and Prof. Reinhard Bürger

Table of contents

The Recombination Hotspot Paradox

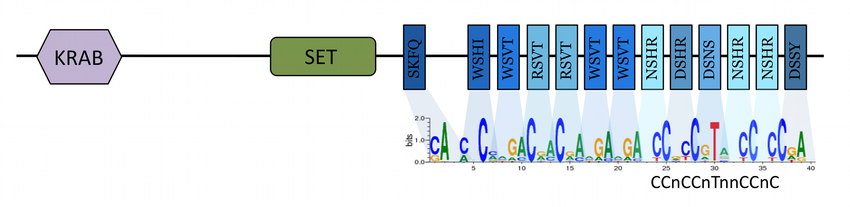

In many species, recombination does not occur uniformly throughout the genome; rather, it usually concentrates in areas of high crossing-over activity called Recombination Hotspots. There are two kinds of such hotspots. In some taxa like birds, recombination concentrates near Transcription Start Sites. In these cases, the mechanism of recombination localization is thought to be passive: crossing-over happens in these areas as the protein machinery takes advantage of open chromatin state associated with the initiation of transcription. In other taxa such as the vast majority of mammals, recombination localization is actively determined by a protein called PRDM9. This protein, whose structure has now been determined, uses its highly variable zinc-finger subdomains to recognize and bind specific target sequences in the genome. Once bound, PRDM9 facilitates the opening of chromatin and recruits the crossing-over machinery.

Interestingly, this recombination-determination mechanism means that recombination hotspots are self-destructive in nature. Indeed, crossing-over can result in the biased gene conversion of the target allele bound by PRDM9 into the homologous allele. As PRDM9 is sequence-specific, heterozygosity means that individual hotspots are expected to be progressively eroded, and eventually disappear. Yet, PRDM9-directed hotspots are still alive and going strong in a wide range of vertebrate taxa. This discrepancy between prediction and empirical data is what has been referred to as the Recombination Hotspot Paradox . Current resolution of the paradox relies on selection for crossing-overs. Indeed, it has been shown that a reduction in the number of crossing-overs can lead to aneuploidy: crossing-overs seem to be involved in the stabilization of the pairing of homologous chromosomes in Prophase I, allowing for their correct segregation. If selection for crossing-over is very strong, models predict that it should act against biaised gene conversion and maintain hotspots. However, this seems to require unrealistic selection intensity, and is in contradiction with empirical data that show that PRDM9, hotspot localization and overall recombination landscapes are all rapidly evolving. If selection is mild, the "Red Queen Theory of Recombination Hotspots" predicts that while individual hotspots indeed "die" from biased gene conversion, PRDM9 sequence evolves to "give birth" to new recombination hotspots at alternative target sites. It is important to note that current resolution of the paradox critically relies on the availability of alternative PRDM9 sequences able to bind new sets of targets. This availability has often been supposed, though it may be not that clear. Indeed, suitable target sequences must: (i) be present in sufficient numbers in the genome, (ii) exist all throughout the genome, in every chromosome, and (iii) not be present in unsuitable locations for crossing-over, such as exons or regulatory sequences. In finite genomes, chances are that the number of alternative target sequence is limited. Arguably, the evolutionary process suggested by the Red Queen model would rapidly exhaust them. In some way, it seems that the Red Queen does not resolve the paradox, but merely push back the necessary resolution.

Death and Resuscitation of Recombination Hotspots

To better understand the evolutionary dynamics of PRDM9-directed recombination hotspots, we build the first model formally taking into account:

allele matches between PRDM9 and target sequences

gene conversion at target loci

selection for crossing-over

mutation at PRDM9 and target sequences

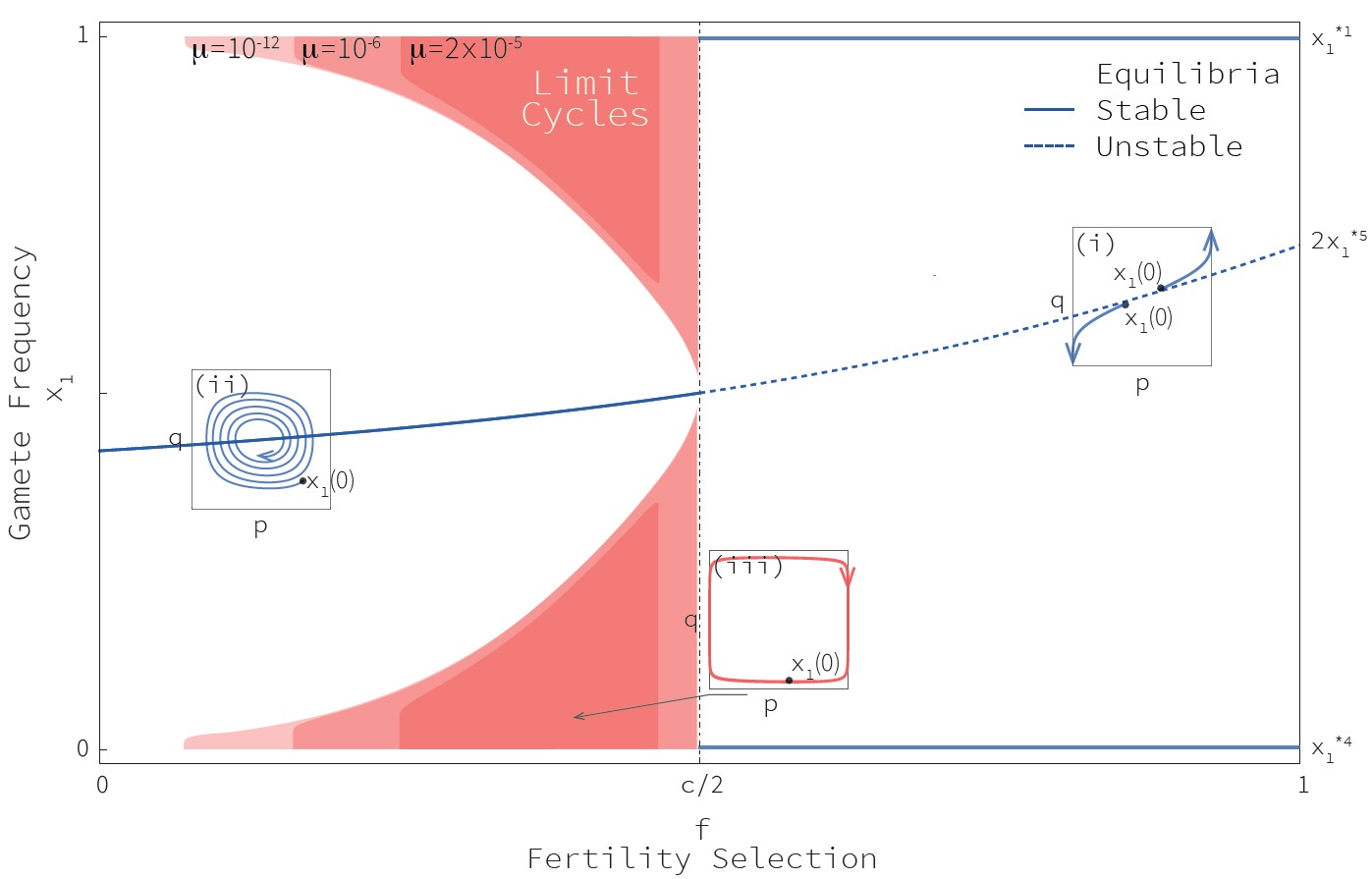

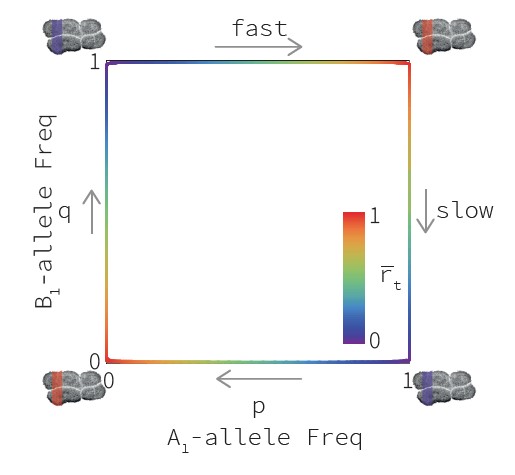

The dynamics of the resulting system can be observed on Fig. 2. We deciphered 3 possible scenarios:

When selection for crossing-overs is strong (f > c/2, with f the fertility cost of an absence of crossing-overs and c the gene conversion rate), the system converges towards the fixation of one of the hot haplotypes (A1B1 or A2B2: PRDM9 allele matches target allele). This coincides with previous results:under intense selection for crossing-overs, hotspots are maintained and are never eroded.

When selection for crossing-overs is strong (f > c/2) and initial frequencies are within its basin of attraction, the system converges towards an internal equilibrium with intermediary frequencies of all 4 haplotypes.Here an equilibrium is found between the opposing forces of selection and conversion: hotspots converge to a mild state. This does not fit empirical data of rapidly evolving recombination landscapes.

Otherwise, if initial frequencies are sufficiently extreme, we observe that the equilibrium found between selection and conversion is dynamical

Fig. 3 gives an idea of what happens in this latter case. We see that hot haplotypes are converted into cold haplotypes (for example, A1B1 into A1B2).

Then, however, selection for crossing-overs rescue the hotspot, driving the spread of an alternative PRDM9 allele that binds the converted target allele (for example,

A2 spreads in response of the conversion of A1B1 into A1B2; now, A2B2 is the dominant, hot haplotype).

The Red Queen theory is correct in arguing that selection for alternative PRDM9 alleles is responsible for restoring crossing-over levels. However, we show here

that there is no need for selecting for PRDM9 alleles that bind new sets of targets. Instead, we argue that PRDM9 should change to bind now cold, but previously hot

targets. Our model is compaible with empirical data on rapidly evolving PRDM9 and recombination landscapes, without requiring constantly finding new targets

to bind.

Rapidly evolving Recombination Landscapes

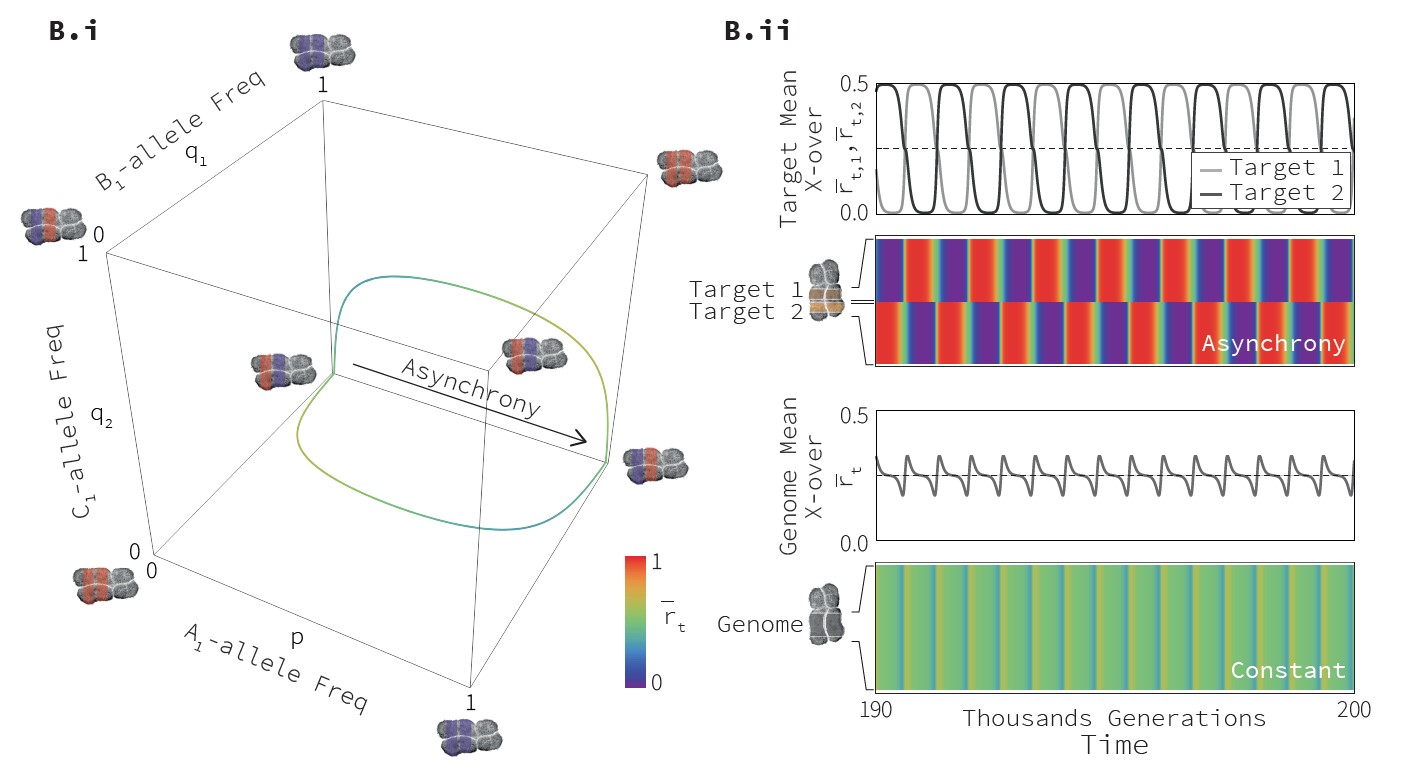

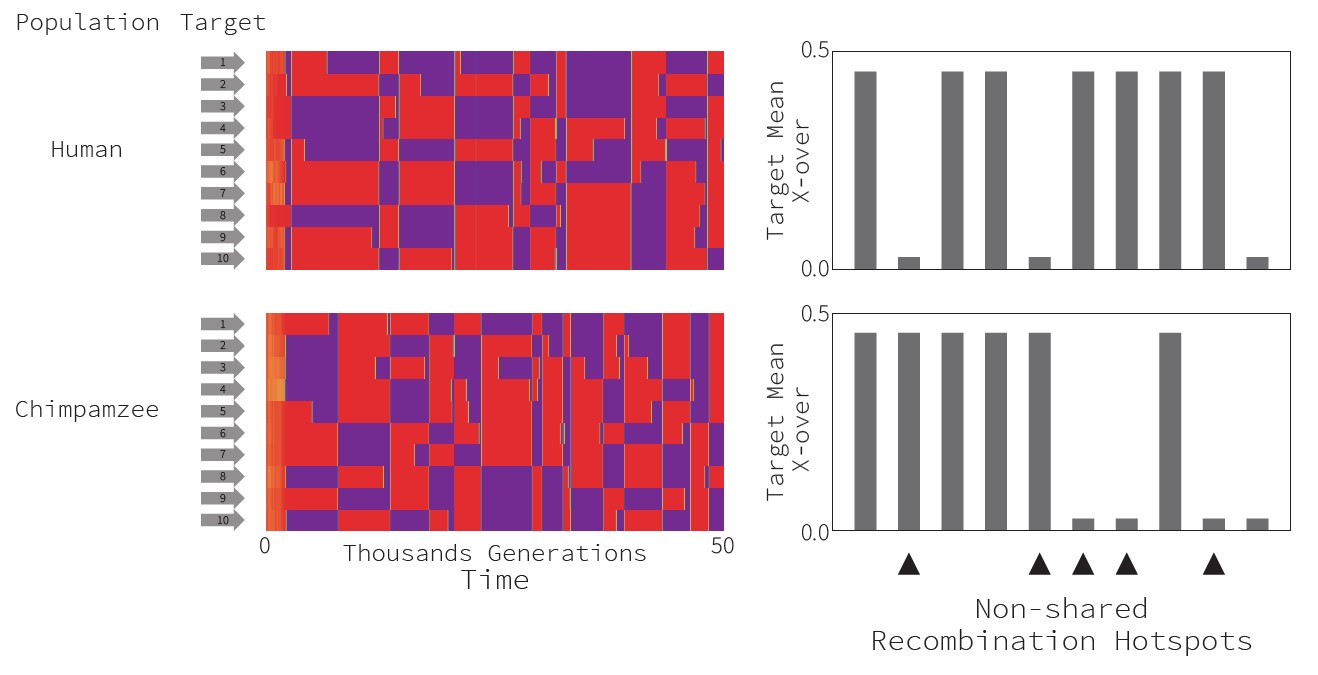

We ran numerical simulations of this model with a varying number of target loci. An example of results is shown on Fig. XX. We see that in stochastic

simulations, each target locus fluctuates between hot and cold states, while overall mean crossing-over rates are much more stable.

Interestingly, we see that two simulations with the same sets of loci and with the same initial conditions rapidly diverge, showing at any given time different

combinations of hot targets. As such, our model is compatible with the observation that closely-related species exhibit very different

recombination landscape: even though they use overall the same set of targets, the actual combinations of hotspots can be very different.

Mathematical analysis shows that a modifier allele that increases mutation rates of PRDM9 relative to the target is selectively favored.

Interestingly, this is not necessarily because such an allele increases individuals' fitness; rather, it is due to linkage effects.

Evolutionary origin of PRDM9

Ongoing top-secret work, more in the upcoming months.

Published Articles

-

The Recombination Hotspot Paradox: Co-evolution between PRDM9 and its target sites

Francisco Úbeda, Frederic Fyon, Reinhard Bürger (2023) Theoretical Population Biology 153: 69-90

DOI: 10.1016/j.tpb.2023.07.001